PART ONE - Probing the Complexity

Is economic growth as we know it past its prime? On our finite, living planet, endless economic growth is chipping away the ecological fabric of life. We see it happening—and we despair when it’s ignored.

Its counter, ‘degrowth’ is a sustainability concept for global well-being, where we design for life: not just human life, all life. But is degrowth a paradigm shift that’s too radical for business and government, both of which still tightly anchor success to economic growth? [1]

I wonder if the tension between growth and degrowth could be the very issue that defeats the idea there’s #NoProblemTooBig to tackle and leave the world better for what we’ve done?

Crikey I hope not… (I’ll have to champion a new slogan.)

In this article, I explore this entangled issue one step after another as it occurs to me and see where we get to - like an early morning walk.

I don’t expect an answer in a first attempt, rather I’ll approach this by laying out my thinking as I go and see if we attain at least a sense of some progress.

[1] Kelsey Piper’s article “Can we save the planet by shrinking the economy?” offers a useful introduction and perspective, Vox online 3 Aug 2021: https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/22408556/save-planet-shrink-economy-degrowth

Context: It’s an Entangled Complexity

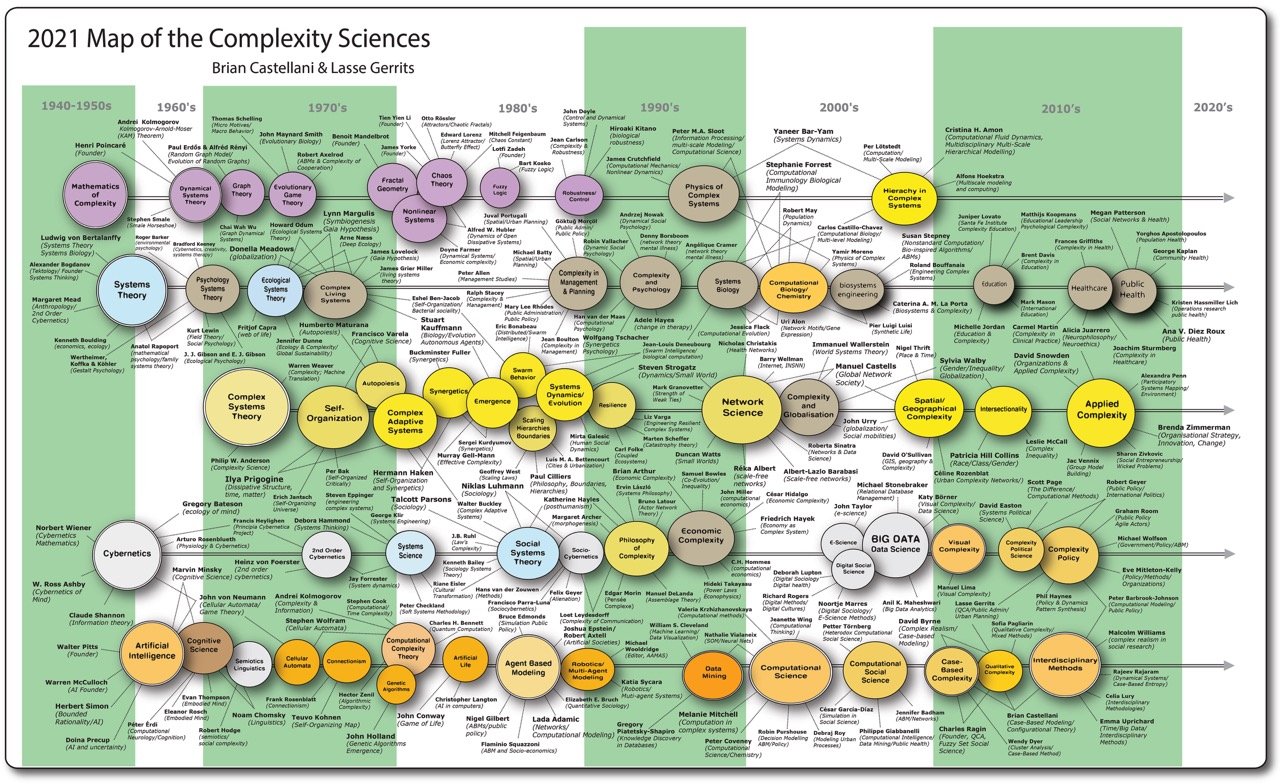

When it comes to complexity, there’s a myriad of places where one could start. The field that had its origins back in the 1940s and developed in so many extraordinary ways that it’s worth having a look at the map of complexity sciences created by Prof. Brian Castellini and Lasse Gerrits of Kent State University [2] just to get a sense of the scope and scale of thinking available to us.

2021 Map of the Complexity Sciences by Castellani and Gerrits

Of it, Castellini writes:

“First, each claims to offer, in its own way, a provocative prescription for what currently ails social inquiry. Second, and despite differences, each grounds its prescription in a similar concern with social complexity. In fact, when combined, these innovations have been hailed as a revolution in thinking – a paradigm shift, if you will, that has arrived, just in time, for the new globalized society in which we now live … [noting] the British Sociologist, Urry called this paradigm shift and its evolving tangle with the social sciences the complexity turn [which] he dates to the late 1990s.” [3]

It’s a daunting picture to say the least. So many great names making a distinguished contribution to thinking. Each name is a lifetime contribution.

And some great names not included - for example, Professor Mike Jackson’s work on Critical Systems Thinking, which offers detailed insights of the theory and application of many methodological approaches to addressing complexity with systemic intervention. Nor does it include the works of people like Daniel Kahneman on judgement, decision making and behavioural economics, or Mariana Mazzucato on innovation and public value, or - more recently - the work of Dr Tyson Yunkaporta on indigenous knowledge systems, with insights on how western thinking and practices drive engagement in precisely the wrong direction.

[2] Map of Complexity Sciences (JPEG version) https://www.art-sciencefactory.com/MAP2021Sharing.jpg

[3] See Brian Castellini’s blog: https://www.theoryculturesociety.org/blog/brian-castellani-on-the-complexity-sciences

A Mentor’s Guidance on Where to Start

When I first started my journey into systems sciences in 1996, I read all I could find from Professor Peter Checkland whose eminent contribution in soft systems methodology were invaluable in approaching a major task I led on integrating diversity across several concurrent research enquiries from technology, physiology, psychology, professional mastery, command and leadership.

Checkland’s message rings clear now:

“It matters less where you start. It matters more that you start.”

Thank you Professor. Now let’s turn and face the headwind.

Tack 1: Cynefin Framework

Let’s start with Dave Snowden’s work on the Cynefin framework that helps leaders make sense of reality by classifying the nature of the problem and applying different decision-making models tailored in each of its five elements. [4]

The Cynefin Framework, Cynefin Co.

I see the ideas of growth and degrowth as complex domains. Each has enabling constraints - frameworks exist for the theory and practice of economic and sustainability undertakings. Each has nested sub-systems of a complicated nature where governing constraints exist. For example, governing the monetary and fiscal practices, or the extraction of resources, and consequences for bad behaviour. At their macro level, complex.

I'd toyed with the idea that growth and degrowth are both chaotic, but that would mean assessing the current regulatory constraints as ineffective. They're not. They're doing what they've been designed to do - support those who benefit most from them.

The Cynefin decision model for complex systems is to probe with ‘safe to fail’ experiments, sense to see what happens, and respond.

Speaking at the International Symposium of the International Council of Systems Engineering #INCOSEIS in Dublin on 3 July 2014, Dave Snowden said complexity deals with systems that are entangled in weak and strong patterns, that are so entangled we don’t have predictive capacity. (I imagine that's a bit of a bugger for market analysts looking for profit growth; and wonder do they know what they're ignoring to make their estimates fit their predictive models?)

Therefore, Snowden reminds us, we have to act in the system and see what patterns emerge, not to set and drive for targets but see what vector-based patterns emerge to guide our direction and speed of change. (When I hear Dave talking about this I think of a meteorological map of wind vectors, that we get to define in our decision making.)

Snowden also gave an overview of his more recent developments on what he calls ‘estuarine mapping’ as a tool to map the environment (substrate) you’re operating in, identify potential changes in the environment and then act to reset one’s environment to increase probability of success.

Estuarine mapping is a tough challenge will be better suited to a community of contributions. With this series of articles being a thought experiment, experienced only as I write this post, so I’m placing that probing idea on hold for the moment.

[4] Dave Snowden’s short video introduction here: https://thecynefin.co/about-us/about-cynefin-framework/

Tack 2: Take a Different Look at the Topic

Instead, I’m drawn to an idea shared by another speaker at #INCOSEIS that might just be the key to navigating the growth vs. degrowth dilemma.

The idea is this: Imagine growth being about “getting rid of stupid stuff to make things easier to use”and, I would add, to make life easier to live.

Growth on those terms would favour everyone.

That idea of “getting rid of stupid stuff” was shared by Professor Kathryn Cormican, Professor of Systems Engineering at the University of Galway in Ireland during her keynote address to close the International Symposium on Systems Engineering last week in Dublin.

It’s an astute idea, which helps connect other insights from #INCOSEIS.

First, to be fair to Professor Cormican, I should share a little of the ‘meat’ she had layered around that ‘bone’:

Industry 5.0 will deliver mass personalisation, harnessing human creativity and robotics to find, she suggests, an optimal balance between efficiency and productivity for improved social well-being.

The world needs more systems-aware leaders: Personalisation demands systemic understanding borne of systems thinking and complexity science. (I’m quietly excited by this realisation, but despair at the slow uptake.)

The biggest challenge for systems engineers is to put more focus on the socio part of socio-technical systems, invoking a shift in attention:

From what we know: Technology driving development of products which then generate experiences to which customers attach meaning.

To it’s inverse: In an Industry 5.0 world, people most desire meaning in life, seeking experiences which utilise products that drive the technology requirements.

Cormican’s inversion is powerful. It’s powerful for at least three reasons:

Starting with meaning instead of technology helps humans rid themselves of “stupid stuff” - the 80% of features we never knew we wanted and never use. Meaning also provokes deeper focus on WHO over WHAT.

It invokes a diversity of perspectives from a diversity of people. There’s more than one user involved. From designer, maker, selector, installer, end-user, maintainer, and the payer… and there may be many more who will care deeply about the design, development, production, use and disposal of Industry 5.0 developments. Each person involved in every stage brings perspective on how to ‘get rid of the stupid stuff’.

It demands empathy from every perspective. The development process will require greater vulnerability to show early prototypes sooner and gain feedback from these multiple perspectives.

Cormican’s messages add value to the quest between growth vs. degrowth, as they help us find the next right thing to do in the present environment by probing an enterprise to:

Place most value on meaning, and work from there

Engage widely to understand experiences of multiple users

Bring multiple perspectives into ‘getting rid of the stupid stuff’

Test early and evaluating often to deliver great experiences without the stupid stuff getting in the way.

Rinse and repeat the personalisation process en masse.

Successful adaptations of the process occur as learning emerges from your:

Sensing, particularly if you’ve created a ‘safe to fail’ environment you will increase the probability of success for sense making from multiple perspectives with each probe, and,

Response-ability, particularly in timely adjustments to the mix of people, methods, tools and information at your / their disposal, to quickly adapt to the emerging constraints and novelty you face (without adding ‘stupid stuff’ that impairs growth.

In essence, cutting out the “stupid stuff” paves the way for growth that truly matters—growth of meaningful experiences, their products and technologies.

(Ha… Whether it was intentional or not, I like this Industry 5.0 alignment with ‘degrowth’ direction. Although I’d prefer to see an emphasis in the Industry 5.0 language on efficacy: doing the right thing before we get into efficiency and productivity, which carry the baggage of the practices that got us into the state we’re in. More on that in the next Article.)

Intermission

This conversation on growth vs, degrowth continues in two more parts, when we consider:

In Part 2: Probing Leadership and Decision Making

Lessons for leadership in delivering ‘big things’ with insights from Professor Patrick Godfrey on the development and construction of London Heathrow Terminal 5: the ‘stupid stuff’ they got rid of and what distinguished the leadership behaviour.

Reprising Professor Peter Checkland's mentoring on decision criteria - his 5 E’s – and its implications for the growth-degrowth conversation.

The value of a Leadership Covenant to anchor direction and behaviour and guide decision making across an enterprise.

In Part 3: Probing Lessons from Systems Studies

Further insights from the #INCOSEIS conference that helps us think more about increasing leadership awareness and practice in systems approaches in exploring growth vs. degrowth, particularly from:

Brian Collins, Emeritus Professor of Engineering Policy at University College London, who gave the opening keynote on ‘Systemic Leadership in a TUNA World’

Mike Jackson, Emeritus Professor, Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull, who invited us to explore 5 different methodological approaches to systems engineering when engaging in complexity.

We'll finish with a brief word in closing on the meeting of the Enterprise Value Working Group at #INCOSEIS, of which I am co-chair. We don’t have answers, but we do have plenty of questions remaining.

Looking forward to continuing this exploration in these next two articles. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts—feel free to reach out and join the conversation online.

Thanks and regards,

Richard